In 1884, Richard Folkard, Jun., wrote a book that definitively traces the connections between the myths and even to the religious beliefs of the ancients through the more modern roots of Christianity. Each chapter of that boo deserves its own post, but I decided to begin by sharing some of the ways that the Fairy world is connect to that of nature and the plant world. Until I moved away and had to leave it there, I allowed my fairy-like concrete cherub to reign over my New Jersey garden.

I, too, associated some kind of magical or special character to my garden fairy, and in 2015, I wrote a short poem to commemorate him:

Cherub Child

by Jacki Kellum

Cherub child, concrete-gray,

Bow your head, bless me, pray.

‘Neath your wings, let me stay,

Walk with me, each day

Also in 2015, I said a few words of explanation about my regard for the cherub that lived in my garden:

“My entire garden is a tribute to my grandmother. I have a large statue of a cherubic angel. I have placed the angel so that I can see it from virtually every spot that I sit or enter my garden. I can even see it through the glass door of my current sunroom. That cherubic angel has become symbolic for me. It is the grandmother of my childhood, manifested as the child that I was.:

Copyright Jacki Kellum October 11, 2015

This, of course, simply described my own feelings, but Folkard’s book provides some foundation for why even today, we feel some mystical connection to nature and why that feeling of mysticism is often channeled through our feelings, even if they are very slight, about fairies in our gardens.

Cicely Mary Barker was a British illustrator who created a gorgeous set of Flower Fairies that have added to our imaginations of how a flower fairy might look:

Wikipedia says the following about Mary Cicely Barker:

“Cicely Mary Barker (28 June 1895 – 16 February 1973) was an English illustrator best known for a series of fantasy illustrations depicting fairies and flowers. Barker’s art education began in girlhood with correspondence courses and instruction at the Croydon School of Art. Her earliest professional work included greeting cards and juvenile magazine illustrations, and her first book, Flower Fairies of the Spring, was published in 1923. Similar books were published in the following decades. ;…

“Barker was equally proficient in watercolour, pen and ink, oils, and pastels. Kate Greenaway and the Pre-Raphaelites were the principal influences on her work. She claimed to paint instinctively and rejected artistic theories. Barker died in 1973. Though she published Flower Fairy books with spring, summer, and autumn themes, it wasn’t until 1985 that a winter collection was assembled from her remaining work and published posthumously.;;;

“Fairies became a popular theme in art and literature in the early 20th century following the releases of The Coming of the Fairies by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Peter Pan by J. M. Barrie, and the fairy-themed work of Australian Ida Rentoul Outhwaite. Queen Mary made such themes even more popular by sending Outhwaite postcards to friends during the 1920s. In 1918, Barker produced a postcard series depicting elves and fairies.[2][4]”

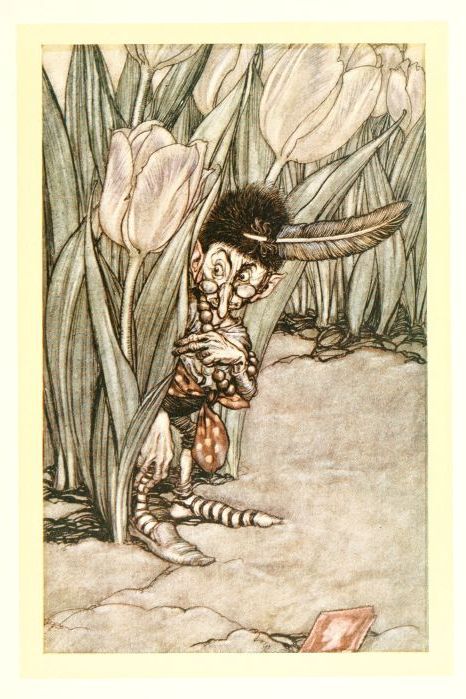

No doubt, everyone is familiar with the Fairy Tinker Bell that J.M. Barrie created for his book: Peter Pan, but in reading Peter Pan in Kensington Garden, I gained an even better understanding of how very much that the fairy lore of his past had actually influenced his writing: I especially love the version of this book that was illustrated by Arthur Rackham, who undoubtedly is the greatest fairy illustrator of all time.

In Kensington Garden, Peter Pan is described as a fairy-like creature who never aged, and who could also fly:

“Well, Peter Pan got out by the window, which had no bars. Standing on the ledge he could see trees far away, which were doubtless the Kensington Gardens, and the moment he saw them he entirely forgot that he was now a little boy in a nightgown, and away he flew, right over the houses to the Gardens. It is wonderful that he could fly without wings, but the place itched tremendously, and—and—perhaps we could all fly if we were as dead-confident-sure of our capacity to do it as was bold Peter Pan that evening.”

But Peter Pan perceived of himself as a baby who has bird-like ability to fly, and he distinguishes himself from other small creatures that were truly fairies who live in the garden,

Illustration by Arthur Rackham

“To Peter’s bewilderment he discovered that every fairy he met fled from him. A band of workmen, who were sawing down a toadstool, rushed away, leaving their tools behind them. A milkmaid turned her pail upside down and hid in it. Soon the Gardens were in an uproar. Crowds of fairies were running this way and that, asking each other stoutly who was afraid; lights were extinguished, doors barricaded, and from the grounds of Queen Mab’s palace came the rub-a-dub of drums, showing that the royal guard had been called out. A regiment of Lancers came charging down the Broad Walk, armed with holly-leaves, with which they jag the enemy horribly in passing. Peter heard the little people crying everywhere that there was a human in the Gardens after Lock-out Time, but he never thought for a moment that he was the human.”

J.M. Barrie was born in 1860 and he lived until 1937, and thereby, he lived at nearly the same time that Cicely Mary Barker lived, But the existence of a fairy mythology long pre-dated either of them.

Richard Folkard says the following about the belief in fairies during a more ancient time:

CHAPTER VI.

Plants of the Fairies and Naiades.

“CENTURIES before Milton wrote that “Millions of spiritual creatures walk the earth unseen, both when we wake, and when we sleep,” our Saxon ancestors, whilst yet they inhabited the forests of Germany, believed in the existence of a diminutive race of beings—the “missing link” between men and spirits—to whom they attributed extraordinary actions, far exceeding the capabilities of human art. Moreover, we have it on the authority of the father of English poetry that long, long ago, in those wondrous times when giants and dwarfs still deigned to live in the same countries as ordinary human beings,

‘In the olde dayes of King Artour,Of which the Bretons speken gret honour,All was this land fulfilled of faerie;The Elf-quene and hire joly compaynieDanced full oft in many a grene mede.This was the old opinion as I rede.’

“The Esthonians believe that during a thunder-storm, and in order to escape from the lightning, the timorous Elves burrow several feet beneath the roots of the trees they inhabit. As a rule these forest Elves are good-natured: if they are not offended, not only will they abstain from harming men, but they will even do them a good turn, and teach them some of the mysteries of nature, of which they possess the secret.

“The Elves were in former days thought to practise works of mercy in the woods, and a certain sympathetic affinity with trees became thus propagated in the popular faith. The country-folk were careful not to offend the trees that were inhabited by Fairies, and they never sought to surprise the Elfin people in their mysterious retreats, for they dreaded the power of these invisible creatures to cause ill-luck or some unfortunate malady to fall on those against whom they had a spite. Even deaths were sometimes laid at their door.

“A German legend relates that as a peasant woman one day tried to uproot the stump of an old tree in a Fir forest, she became so feeble that at last she could scarcely manage to walk. Suddenly, while endeavouring to crawl to her home, a mysterious-looking man appeared in the path before the poor woman, and upon hearing what was the matter with her, he at once remarked that she had wounded an Elf. If the Elf got well, so would she; but if the Elf should unfortunately perish, she would also assuredly die. The stump of the old Fir-tree was the abode of an Elf, and in endeavouring to uproot it, the woman had unintentionally injured the little creature. The words of the mysterious personage proved too true. The peasant languished for some time, but drooped and died on the same day as the wounded Elf. To this day, in the vast forests of Germany and Russia, instead of uprooting old Firs, the foresters, remembering the Elfish superstition, always chop them down above the roots.

“In the Indian legend of Sâvitri, the youthful Satyavant, while felling a tree, perspires inordinately, is overcome with weakness, sinks exhausted, and dies. He had mortally wounded the Elf of the tree. Since the days of Æsop it has become a saying that Death has a weakness for woodmen.

“In our own land, Oaks have always been deemed the favourite abodes of Elves, and wayfarers, upon approaching groves reputed to be haunted by them, used to think it judicious to turn their coats for good luck. Thus Bishop Corbet, in his Iter Boreale, writes:—

‘William foundA means for our deliverance: ‘Turn your cloakes,’Quoth he, ‘for Pucke is busy in these Oakes;If ever we at Bosworth will be found,Then turn your cloakes, for this is Fairy ground.’

‘Would you the Fairy regions see,Hence to the greenwoods run with me;From mortals safe the livelong night,There countless feats the Fays delight.’ —Leftly.

“In the Isle of Man the Fairies or Elves used to be seen hopping from trees and skipping from bough to bough, whilst wending their way to the Fairy midnight haunts.

“In such esteem were they held by the country folk of Devon and Cornwall, that to ensure their friendship and good offices, the Fairies, or Pixies, used formerly to have a certain share of the fruit crop set apart for their special consumption.

Hans Christian Andersen tells of a certain Rose Elf who was instrumental in punishing the murderer of a beautiful young maiden to whom he was attached. The Rose, in olden times, was reputed to be under the especial protection of Elves, Fairies, and Dwarfs, whose sovereign, Laurin, carefully guarded the Rose-garden.

The Moss Woman

‘A Moss-woman!’ the hay-makers cry,And over the fields in terror they fly.She is loosely clad from neck to footIn a mantle of Moss from the Maple’s root,And like Lichen grey on its stem that growsIs the hair that over her mantle flows.Her skin, like the Maple-rind, is hard,Brown and ridgy, and furrowed and scarred;And each feature flat, like the bark we see,Where a bough has been lopped from the bole of a tree,When the newer bark has crept healingly round,And laps o’er the edge of the open wound;Her knotty, root-like feet are bare,And her height is an ell from heel to hair.’

“The Still-Folk of Central Germany were another tribe of the Fairy Kingdom: they inhabited the interior of hills, in which they had their spacious halls and strong rooms filled with gold, silver, and precious stones—the entrance to which was only obtained by mortals by means of the Luck-flower, or the Key-flower (Schlüsselblume). They held communication with the outer world, like the Trolls of Scandinavia, through certain springs or wells, which possessed great virtues: not only did they give extraordinary growth and fruitfulness to all trees and shrubs that grew near them, whose roots could drink of their waters, or whose leaves be sprinkled with the dews condensed from their vapours, but for certain human diseases they formed a sovereign remedy.

“In Monmouthshire, in years gone by, there existed a good Fairy, or Procca, who was wont to appear to Welshmen in the guise of a handful of loose dried grass, rolling and gambolling before the wind.

Fairy Revels.

The English Fays and Fairies, the Pixies of Devon—

according to the old pastoral poets, were wont to bestir themselves soon after sunset—a time of indistinctness and gloomy grandeur, when the moonbeams gleam fitfully through the wind-stirred branches of their sylvan retreats, and when sighs and murmurings are indistinctly heard around, which whisper to the listener of unseen beings. But it is at midnight that the whole Fairy kingdom is alive: then it is that the faint music of the blue Harebell is heard ringing out the call to the Elfin meet:

Like the Witches, Fairies dearly love to ride to the trysting-place on an aerial steed. A straw, a blade of Grass, a Fern, a Rush, or a Cabbage-stalk, alike serve the purpose of the little people. Mounted on such simple steeds, each joyous Elf sings—

Arrived at the spot selected for the Fairy revels—mayhap, “a bank whereon the wild Thyme blows, where Oxlips and the nodding Violet grows”—the gay throng wend their way to a grassy link or neighbouring pasture, and there the merry Elves trip and pace the dewy green sward with their printless feet, causing those dark green circles that are known to mortals as “Fairy Rings.”

Old William Browne depicts a Fairy trysting-place as being in proximity to one of their sylvan haunts, and moreover gives us an insight into the proceedings of the Fays and their queen at one of their meetings. He says:—

St. John’s Eve was undoubtedly chosen for important communication between the distant Elfin groves and the settlements of men, on account of its mildness, brightness, and unequalled beauty. Has not Shakspeare told us, in his ‘Midsummer’s Night’s Dream,’ of the doings, on this night, of Oberon, Ariel, Puck, Titania, and her Fairy followers?—

Yet timorous and ill-informed folk, mistrusting the kindly disposition of Elves and Fairies, took precautions for excluding Elfin visitors from their dwellings by hanging over their doors boughs of St. John’s Wort, gathered at midnight on St. John’s Eve. A more kindly feeling, however, seems to have prevailed at Christmas time, when boughs of evergreen were everywhere hung in houses in order that the poor frost-bitten Elves of the trees might hide themselves therein, and thus pass the bleak winter in hospitable shelter.

Fairy Plants.

In Devonshire the flowers of Stitchwort are known as Pixies.

Of plants which are specially affected by the Fairies, first mention should be made of the Elf Grass (Vesleria cærulea), known in Germany as Elfenkraut or Elfgras. This is the Grass forming the Fairy Rings, round which, with aerial footsteps, have danced

The Cowslip, or Fairy Cup, Shakspeare tells us forms the couch of Ariel—the “dainty Ariel” who has so sweetly sung of his Fairy life—

The fine small crimson drops in the Cowslip’s chalice are said to possess the rare virtue of preserving, and even of restoring, youthful bloom and beauty; for these ruddy spots are fairy favours, and therefore have enchanted value. Shakspeare says of this flower of the Fays:—

Another of the flowers made potent use of by the Fairies of Shakspeare is the Pansy—that “little Western flower” which Oberon bade Puck procure:—

The Anemone, or Wind-flower, is a recognised Fairy blossom. The crimson marks on its petals have been painted there by fairy hands; and, in wet weather, it affords shelter to benighted Elves, who are glad to seek shelter beneath its down-turned petals. Tulips are greatly esteemed by the Fairy folk, who utilise them as cradles in which to rock the infant Elves to sleep.

The Fairy Flax (Linum catharticum) is, from its extreme delicacy, selected by the Fays as the substance to be woven for their raiment. The Pyrus Japonica is the Fairies’ Fire. Fairy-Butter (Tremella arborea and albida) is a yellowish gelatinous substance, found upon rotten wood or fallen timber, and which is popularly supposed to be made in the night, and scattered about by the Fairies. The Pezita, an exquisite scarlet Fungus cup, which grows on pieces of broken stick, and is to be found in dry ditches and hedge-sides, is the Fairies’ Bath.

To yellow flowers growing in hedgerows, the Fairies have a special dislike, and will never frequent a place where they abound; but it is notorious that they are passionately fond of most flowers. It is part of their mission to give to each maturing blossom its proper hue, to guide creepers and climbing plants, and to teach young plants to move with befitting grace.

But the Foxglove is the especial delight of the Fairy tribe: it is the Fairy plant par excellence. When it bends its tall stalks the Foxglove is making its obeisance to its tiny masters, or preparing to receive some little Elf who wishes to hide himself in the safe retreat afforded by its accommodating bells. In Ireland this flower is called Lusmore, or the Great Herb. It is there the Fairy Cap, whilst in Wales it becomes the Goblin’s Gloves.

As the Foxglove is the special flower of the Fairies, so is a four-leaved Clover their peculiar herb. It is believed only to grow in places frequented by the Elfin tribe, and to be gifted by them with magic power.

The maiden whose search has been successful for this diminutive plant becomes at once joyous and light-hearted, for she knows that she will assuredly see her true love ere the day is over. The four-leaved Clover is the only plant that will enable its wearer to see the Fairies—it is a magic talisman whereby to gain admittance to the Fairy kingdom,[8] and unless armed with this potent herb, the only other means available to mortals who wish to make the acquaintance of the Fairies is to procure a supply of a certain precious unguent prepared according to the receipt of a celebrated alchymist, which, applied to the visual orbs, is said to enable anyone with a clear conscience to behold without difficulty or danger the most potent Fairy or Spirit he may anywhere encounter. The following is the form of the preparation:—

“R. A pint of Sallet-oyle, and put it into a vial-glasse; but first wash it with Rose-water and Marygolde water; the flowers to be gathered towards the east. Wash it till the oyle come white; then put it into the glasse, ut supra: and then put thereto the budds of Holyhocke, the flowers of Marygolde, the flowers or toppers of Wild Thyme, the budds of young Hazle: and the Thyme must be gathered neare the side of a hill where Fayries used to be: and take the grasse of a Fayrie throne. Then all these put into the oyle into the glasse: and sette it to dissolve three dayes in the sunne, and then keep it for thy use; ut supra.”—[Ashmolean MSS.].

Plants of the Water Nymphs and Fays.

Certain of the Fairy community frequented the vicinity of pools, and the banks of streams and rivers. Ben Jonson tells of “Span-long Elves that dance about a pool;” and Stagnelius asks—

Of this family are the Russalkis, river nymphs of Southern Russia, who inhabit the alluvial islands studding the winding river, or dwell in detached coppices fringing the banks, or construct for themselves homes woven of flowering Reeds and green Willow-boughs.

The Swedes delight to tell of the Strömkarl, or boy of the stream, a mystic being who haunts brooks and rivulets, and sits on the silvery waves at moonlight, playing his harp to the Elves and Fays who dance on the flowery margin, in obedience to his summons—

The Græco-Latin Naiades, or Water-nymphs, were also of this family: they generally inhabited the country, and resorted to the woods or meadows near the stream over which they presided. It was in some such locality on the Asiatic coast that the ill-fated Hylas was carried off by Isis and the River-nymphs, whilst obtaining water from a fountain.

These inferior deities were held in great veneration, and received from their votaries offerings of fruit and flowers; animal sacrifices were also made to them, with libations of wine, honey, oil, and milk; and they were crowned with Sedges and flowers. A remnant of these customs was to be seen in the practice which formerly prevailed in this country of sprinkling rivers with flowers on Holy Thursday. Milton, in his ‘Comus,’ tells us that, in honour of Sabrina, the Nymph of the Severn—

A belief in the existence of good spirits who watched and guarded wells, springs and streams, was common to the whole Aryan race. On the 13th of October the Romans celebrated at the Porta Fontinalis a festival in honour of the Nymphs who presided over fountains and wells: this was termed the Fontinalia, and during the ceremonies wells and fountains were ornamented with garlands. To this day the old heathen custom of dressing and adorning wells is extant, although saints and martyrs have long since taken the place of the Naiades and Water-nymphs as patrons. In England, well-dressing at Ascension-tide is still practised, and some particulars of the ancient custom will be found in the chapter on Floral Ceremonies.

Pilgrimages are made to many holy wells and springs in the United Kingdom, for the purpose of curing certain diseases by the virtues contained in their waters, or to dress these health-restoring fountains with garlands and posies of flowers. It is not surprising to find Ben Jonson saying that round such “virtuous” wells the Fairies are fond of assembling, and dancing their rounds, lighted by the pale moonshine—

In Cornwall pilgrimages are made in May to certain wells situated close to old blasted Oaks, where the frequenters suspend rags to the branches as a preservative against sorcery and a propitiation to the Fairies, who are thought to be fond of repairing at night to the vicinity of the wells. From St. Mungo’s Well at Huntly, in Scotland, the people carry away bottles of water, as a talisman against the enmity of the Fairies, who are supposed to hold their revels at the Elfin Croft close by, and are prone to resent the intrusion of mortals.

CHAPTER VII.

Sylvans, Wood Nymphs, and Tree Spirits.

CLOSELY allied to the Fairy family, the Well Fays, and the Naiades, are the Sylvans of the Græco-Roman mythology, which everywhere depicts groves and forests as the dwelling-places and resorts of merry bands of Dryads, Nymphs, Fauns, Satyrs, and other light-hearted frequenters of the woods. Mindful of this, Horace, when extolling the joys and peacefulness of sylvan retirement, sings:—

The Dryads were young and beautiful nymphs who were regarded as semi-goddesses. Deriving their name from the Greek word drus, a tree, they were conceived to dwell in trees, groves, and forests, and, according to tradition, were wont to inflict injuries upon people who dared to injure the trees they inhabited and specially protected. Notwithstanding this, however, they frequently quitted their leafy habitations, to wander at will and mingle with the wood nymphs in their rural sports and dances. They are represented veiled and crowned with flowers. Such a sylvan deity Rinaldo saw in the Enchanted Forest, when

The Hamadryads were only females to the waist, their lower parts merging into the trunks and roots of trees. Their life and power terminated with the existence of the tree over which they presided. These sylvan deities had long flowing hair, and bore in their hands axes wherewith to protect the tree with which they were associated and on the existence of which their own life depended. The trees of the Hamadryads usually grew in some secluded spot, remote from human habitations and unknown to men, where

The rustic deities, called by the Greeks Satyrs, and by the Romans, Fauns, had the legs, feet, and ears of goats, and the rest of the body human. These Fauns, according to the traditions of the Romans, presided over vegetation, and to them the country folk gave anything they had a mind to ask—bunches of Grapes, ears of Wheat, and all sorts of fruit. The food of the Satyrs was believed, by the early Romans, to be the root of the Orchis or Satyrion; its aphrodisiacal qualities exciting them to those excesses to which they are stated to have been so strongly addicted.

A Roumanian legend[9] tells of a beauteous sylvan nymph called the Daughter of the Laurel, who is evidently akin to the Dryads and wood nymphs; and Mr. Ralston, in an article on ‘Forest and Field Myths,’[10] gives the following variation of the story:—“There was once a childless wife who used to lament, saying, ‘If only I had a child, were it but a Laurel berry!’ And heaven sent her a golden Laurel berry; but its value was not recognised, and it was thrown away. From it sprang a Laurel-tree, which gleamed with golden twigs. At it a prince, while following the chase, wondered greatly; and determining to return to it, he ordered his cook to prepare a dinner for him beneath its shade. He was obeyed. But during the temporary absence of the cook, the tree opened, and forth came a fair maiden who strewed a handful of salt over the viands, and returned into the tree, which immediately closed upon her. The prince returned and scolded the cook for over-salting the dinner. The cook declared his innocence; but in vain. The next day just the same occurred. So on the third day the prince kept watch. The tree opened, and the maiden came forth. But before she could return into the tree, the prince caught hold of her and carried her off. After a time she escaped from him, ran back to the tree, and called upon it to open. But it remained shut. So she had to return to the prince, and after a while he deserted her. It was not till after long wandering that she found him again, and became his loyal consort.” Mr. Ralston says that in Hahn’s opinion the above story is founded on the Hellenic belief in Dryads; but he himself thinks it belongs to an earlier mythological family than the Hellenic, though the Dryad and the Laurel-maiden are undoubtedly kinswomen. “Long before the Dryads and Oreads had received from the sculpturesque Greek mind their perfection of human form and face, trees were credited with woman-like inhabitants, capable of doing good and ill, and with power of their own, apart from those possessed by their supernatural tenants, of banning and blessing. Therefore was it that they were worshipped, and that recourse was had to them for the strengthening of certain rites. Similar ideas and practices still prevail in Asia: survivals of them may yet be found in Europe.”

In Moldavia there lingers the cherished tradition of Mariora Floriora, the Zina (nymph) of the mountains, the Sister of the Flowers, at whose approach the birds awoke and sung merrily, desirous of anticipating her every wish, and the wild flowers exhaled their choicest perfume, and, bowing gently in the wind, proffered every virtue contained in their blossoms. Yielding one day to the fascinations of a mortal, Mariora Floriora gave herself to him, and forgot her flowers, so that the leaves fell yellow and withered, and the flowers drooped their heads and faded. Then they complained to the Sun that the flower nymph no longer tended them, but rambled over the mountains and meadows absorbed with her mortal lover. So a Zméu (evil spirit) was sent, who seized her in his arms, and carried her away over the mountain. Now she is never seen; but when the moon is shining on a serene night, her plaintive murmurs are sometimes heard in the caverns of the mountain.

Sacred Groves and their Denizens.

The Roman goddess Pomona, we are told by Ovid, came of the family of Dryads, or sylvan deities; and although “the Nymph frequented not the fluttering stream, nor meads, the subject of a virgin’s dream,” yet—

As a deity, Pomona presided over gardens and all sorts of fruit-trees, and was honoured with a temple in Rome, and a regular priest, called Flamen Pomonalis, who offered sacrifices to her divinity for the preservation of fruit. In this respect Pomona differed from the other Sylvans, who were only regarded as semi-gods and goddesses. The worship of these sylvan deities, however, by the Greeks and Romans caused them to regard with reverence and respect their nemorous habitations. Hence we find that, like the Egyptians, they were fond of surrounding their temples and fanes with groves and woods, which in time came to be regarded as sacred as the temples themselves. Pliny, speaking of groves, says: “These were of old the temples of the gods; and after that simple but ancient custom, men at this day consecrate the fairest and goodliest trees to some deity or other; nor do we more adore our glittering shrines of gold and ivory than the groves in which, with profound and awful silence, we worship them.” Ancient writers often refer to “vocal forests,”—in their sombre and gloomy recesses, the frighted wayfarer imagined, as the wind soughed and rustled through the dense foliage, that the tree spirits were humming some sportive lay, or—perchance more frequently—chanting weirdly some solemn dirge. The grove which surrounded Jupiter’s Temple at Dodona was supposed to be endowed with the gift of prophecy, and oracles were frequently there delivered by the sacred Oaks.

In course of time each tree of these sacred groves was held to be tenanted, or presided over, either by a god or goddess, or by one of the sylvan semi-deities. Impious was deemed he who dared to profane the sanctity of one of these nemorous retreats, either by damaging or by felling the consecrated trees. Rapin, in his Latin poem on Gardens, says:

When threatened with the woodman’s axe, the tutelary genius of the doomed tree would intercede for its life, the very leaves would sigh and groan, the stalwart trunk tremble with horror. Ovid relates how Erisichthon, a Thessalian, who derided Ceres, and cut down the trees in her sacred groves, was, for his impiety, afflicted with perpetual hunger. Of one huge old Oak the poet says—

But the vindictive Erisichthon bade his hesitating servants fell the venerable tree, and, dissatisfied with their speed, seized an axe, and approached it, declaring that nothing should save the Oak:—

Tree Spirits.

Ovid, in his ‘Metamorphoses,’ has told us how, after Daphne had been changed into a Laurel, the nymph-tree still panted and heaved her heart; how, when Phaethon’s grief-stricken sisters were transformed into Poplars, they continued to shed tears, which were changed into amber; how Myrrha, metamorphosed into a tree, still wept, in her bitter grief, the precious drops which retain her name; how Dryope, similarly transformed, imparted her life to the branches, which glowed with a human heat; and how the tree into which the nymph Lotis had been changed, shook with sudden horror when its blossoms were plucked and blood welled from the broken stalks. In these poetic conceptions it is easy to see the embodiment of a belief very rife among the Greeks and Romans that trees and shrubs were tenanted in some mysterious manner by spirits. Thus Virgil tells us that when Æneas had travelled far in search of the abodes of the blest—

Nor was this notion confined simply to the Greeks and Romans, for among the ancients generally there existed a wide-spread belief that trees were either the haunts of disembodied spirits, or contained within their material growth the actual spirits themselves. Evelyn tells us that “the Ethnics do still repute all great trees to be divine, and the habitations of souls departed: these the Persians call Pir and Imàm.” The Persians, however, entertaining a profound regard for trees of unusual magnitude, were of opinion that only the spirits of the pure and holy inhabited them.

In this respect they differed from the Indians, who believed that both good and evil spirits dwelt in trees. Thus we read in the story of a Brahmadaitya (a Bengal folk-tale), of a certain Banyan-tree haunted by a number of ghosts who wrung the necks of all who were rash enough to approach the tree during the night. And, in the same tale, we are told of a Vakula-tree (Mimusops Elengi) which was the haunt of a Brahmadaitya (the ghost of a Brahman who dies unmarried), who was a kindly and well-disposed spirit. In another folk-tale we are introduced to the wife of a Brahman who was attacked by a Sankchinni, or female ghost, inhabiting a tree near the Brahman’s house, and thrust by the vindictive ghost into a hole in the trunk. The Rev. Lal Behari Day explains that Sankchinnis or Sankhachurnis are female ghosts of white complexion, who usually stand in the dead of night at the foot of trees. Sometimes these tree-spirits appear to leave their usual sylvan abode and enter into human beings, in which case an exorcist is employed, who detects the presence of the spirit by lighting a piece of Turmeric root, which is an infallible test, as no ghost can put up with the smell of burnt Turmeric.

The Shánárs, aborigines of India, believe that disembodied spirits haunt the earth, dwelling in trees, and taking special delight in forests and solitary places. Against the malignant influence of these wandering spirits, protection is sought in charms of various kinds; the leaves of certain trees being esteemed especially efficacious. Among the Hindus, if an infant refuse its food, and appear to decline in health, the inference is drawn that an evil spirit has taken possession of it. As this demon is supposed to dwell in some particular tree, the mothers of the northern districts of Bengal frequently destroy the unfortunate infant’s life by depositing it in a basket, and hanging the same on the demon’s tree, where it perishes miserably.[11]

In Burmah the worship of Nats, or spirits of nature, is very general. Indeed among the Karens, and numerous other tribes, this spirit-worship is their only form of belief. The shrines of these Nats are often, in the form of cages, suspended in Peepul or other trees—by preference the Le’pan tree, from the wood of which coffins are made. When a Burman starts on a journey, he hangs a bunch of Plantains, or a spray of the sacred Eugenia, on the pole of his buffalo cart, to conciliate any spirit he may intrude upon. The lonely hunter in the forest deposits some Rice, and ties together a few leaves, whenever he comes across some imposing-looking tree, lest there should be a Nat dwelling there. Should there be none, the tied-back leaves will, at any rate, stand in evidence to the Nat or demon who presides over the forest. Some of the Nats or spirits are known far and wide by special or generic names. There is the Hmin Nat who lives in woods, and shakes those he meets so that they go mad. There is the Akakasoh, who lives in the tops of trees; Shekkasoh, who lives in the trunk; and Boomasoh, who dwells contentedly in the roots. The presence of spirits or demons in trees the Burman believes may always be ascertained by the quivering and trembling of the leaves when all around is still.

Schweinfurth, the African explorer, tells us that, at the present day, among the Bongos and the Niam-Niams, woods and forests are regarded with awe as weird and mysterious places, the abodes of supernatural beings. The malignant spirits who are believed to inhabit the dark and gloomy forests, and who inspire the Bongos with extraordinary terror, have, like the Devil, wizards, and witches, a distinctive name: they are called bitâbohs; whilst the sylvan spirits inhabiting groves and woods are known as rangas. Under this last designation are comprised owls of different species, bats, and the ndorr, a small ape, with large red eyes and erect ears, which shuns the light of day, and hides itself in the trunks of trees, from whence it comes forth at night. As a protection against the influence of these malignant spirits of the woods, the Bongos have recourse to certain magical roots which are sold to them by their medicine-men. According to those worthies no one can enter into communication with the wood spirits except by means of certain roots, which enable the possessor to exorcise evil spirits, or give him the power of casting spells. All old people, but especially women, are suspected of having relations, more or less intimate, with the sylvan spirits, and of consulting the malign demons of the woods when they wish to injure any of their neighbours. This belief in evil spirits, which is general among the Bongos and other tribes of Africa, exists also among the Niam-Niams. For the latter, the forest is the abode of invisible beings who are constantly conspiring to injure man; and in the rustling of the foliage they imagine they hear the mysterious dialogues of the ghostly inhabitants of the woods.

The ancient German race, in whom there existed a deep reverence for trees, peopled their groves and forests with a whole troup of Waldgeister, both beneficent and malevolent. A striking example is to be seen in the case of the Elder, in which dwells the Hylde-moer (Elder-mother), or Hylde-vinde (Elder-queen), who avenges all injuries done to the Elder-tree. On this account Elder branches may not be cut until permission has been asked of the Hylde-moer. In Lower Saxony the woodman will, on his bended knee, ask permission of the Elder-tree before cutting it, in these words: “Lady Elder, give me some of thy wood; then will I give thee, also, some of mine when it grows in the forest.” This formula is repeated three times.

Nearly allied to the tree-spirits were the Corn-spirits,[12] which haunted and protected the green or yellow fields. Mr. Ralston tells us that by the popular fancy they were often symbolised under the form of wolves, or of “buckmen,” goat-legged creatures, similar to the classic Satyrs. “When the wind blows the long Grass or waving Corn, German peasants still say, ‘The Grass-wolf’ or ‘The Corn-wolf,’ is abroad! In some places the last sheaf of Rye is left as a shelter to the Roggenwolf, or Rye-wolf, during the winter’s cold; and in many a summer or autumn festive rite, that being is represented by a rustic, who assumes a wolf-like appearance. The Corn-spirit, however, was often symbolised under a human form.”

The belief in the existence of a spirit whose life is bound up in that of the tree it inhabits remains to the present day. There is a wide-spread German belief that if a sick man is passed through a cleft made in a tree, which is immediately afterwards bound up, the man and the tree become mysteriously connected—if the tree flourishes so will the man; but if it withers he will die. Should, however, the tree survive the man, the soul of the latter will inhabit the tree; and (according to Pagan tradition) if the tree be felled and used for ship-building, the dead man’s ghost becomes the haunting genius of the ship. This strange notion may have had its origin in the classic story of the Argonauts and their famous ship. A beam on the prow of the Argo had been cut by Minerva out of the forest of Dodona, where the trees were thought to be inhabited by oracular spirits: hence the beam retained the power of giving oracles to the voyagers, and warned them that they would never reach their country till Jason had been purified of the murder of Absyrtus. There is a story that tells how, when a musician cut a piece of wood from a tree into which a girl had been metamorphosed by her angry mother, he was startled to see blood oozing from the wound. And when he had shaped it into a bow, and played with it upon his violin before her mother, such a heart-rending wail made itself heard, that the mother was struck with remorse, and bitterly repented of her hasty deed. Mr. Ralston quotes a Czekh story of a Nymph who appeared day by day among men, but always went back to her willow by night. She married a mortal, bare him children, and lived happily with him, till at length he cut down her Willow-tree: that moment his wife died. Out of this Willow was made a cradle, which had the power of instantly lulling to sleep the babe she had left behind her; and when the babe became a child, it was able to hold converse with its dead mother by means of a pipe, cut from the twigs growing on the stump, which once had been that mother’s abiding-place.