In my garden, I am continuously searching for the plants that my German grandmother probably grew in her magnificent garden, and I am almost certain that she grew Pink Brandywine tomatoes, which are currently considered to be Heirloom cultivars. My grandmother was born late in the 1890s, and she herself might be considered an heirloom now.

For several years, I lived near the Amish country of Pennsylvania, and once, when I visited there, I commented that the Amish men looked like my grandmother’s brothers. Other than religious and cultural beliefs, the Amish people are very much like my German ancestors, and they are reported to have grown Brandywine tomatoes in Pennsylvania since the late 1800s.

On the University of Arkansas Agriculture Extension website, the following is written about Brandywine tomatoes:

“Just the thought of a juicy bite of a red, ripe tomato is enough to get your mouth watering and make you appreciate the heat of summertime. Unlike most vegetable gardeners, tomato connoisseurs can be a bit snobby. They know their tomatoes and can become downright belligerent if you try to convince them that your favorite tomato is better than theirs. But most experts will agree that Brandywine tomato is one of the best with a great tomatoey flavor.

“The original Brandywine is a large, meaty, pink tomato with coarse, heavy potato-like foliage. Individual fruit weight is up to a pound. A single slice is large enough to cover a hamburger bun. The growth form is indeterminate with plants taking on a rangy appearance as the summer wears on. They are late-producing with the first fruit not appearing for 90 to 100 days, about 30 days later than many cultivars.

“You will probably not find Brandywine in local stores, but it’s a natural for the farmer’s market trade in August. Although the best known of all heirloom vegetables, it does have some flaws. It’s low-yielding, tends to ripen unevenly, have green shoulders, catface and to crack badly if rainfall catches the ripening fruit at the wrong time.”

Most of the old-timer farmers in the Ozarks are familiar with Pink Brandywine, but the old guy who sold me my tomato plants warned me that the Pink Brandywine might not be the best cultivar to grow in my garden. I asked him why, and he responded, “Too rough.”

But I am stubborn, and I was on a quest to find my grandmother’s garden again. Months after i planted my Brandywines, I believe that I agree that Brandywine truly is NOT the best tomato plant for me to grow. I have also learned that when an old Ozark Mountain Farmer tells your something about tomatoes, that I should listen.

Pink Brandywine Tomatoes from Jacki Kellum’s Garden August 28, 2021

Some of my Brandywines cracked around the top of fruit, as you see in the above photo.

Pink Brandywine Tomatoes from Jacki Kellum’s Garden August 28, 2021

All of my Pink Brandywines have green shoulders. By that, I am saying that even when the bottoms of the tomatoes are ripe, the tops remain green.

And inside the tomato, where the green on the top and the red on the bottom merge, the fruit has a brownish color. I know from having been a painter that when red paint merges with green paint, you create brown paint, and the same thing happens with a Pink Brandywine tomato.

Looking again at the photo above, you will see a lot of yellow, which is almost like a core inside the tomato. I am not sure that this is one of the reasons that my old farmer friend called this tomato “rough.”

The tomato has a nice, tomatoey flavor, but I don’t believe that it is the best that I have ever tasted. That same, old Ozarks farmer recommended Arkansas Traveler tomatoes, and next year, I’ll listen.

Brandywine is not a perfect tomato. To reiterate its faults:

- Brandywine is low-yielding.

- Brandywine ripens unevenly.

- Rain might cause Brandywine tomatoes to crack.

- Because of catfacing and green shoulders, the Brandywine is not considered to be a “pretty” cultivar.

But it does have one asset:

- Good tomatoey flavor *******

Here is the worst thing that I discovered from having grown Pink Brandywine, I am pretty sure that it is not the tomato that my grandmother grew. I’m still chasing that Holy Grail, but I’ll grow Pink Brandywine again, and I’ll grow other heirloom tomatoes, too, next year.

I grow heirloom plants because I honor the gardening tradition out of which I grew. I’ll always have some heirloom plants in my garden.

On [August 12], I am watching my Pink Brandywine tomato as it slowly works its way through the ripening process. A watermelon-looking webbing of darker green has scribed itself across the bottoms of the more mature fruits. That darker striping was not there 2 days ago.

By August 20, 2021, one of the tomatoes had begun blush.

By August 28, I had picked the first two of my Pink Brandywines, and I had tasted them, but other fruits were still ripening on the vine.

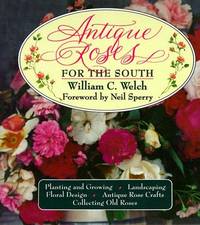

Read what William Welch said about the importance of our ancestors and their influences on out gardens:

“Milk and wine lily, Confederate rose, cockscomb, yellow flags, “Old Blush” rose, blackberry lily . . . Even their names evoke the romance, whimsey, and elegance of their histories. Cherished for their beauty and imbued with meaning, these and many other Southern heirloom plants have been carefully and lovingly passed down generation after generation. Their living legacy preserves the quiet charm and whispery remembrances of gardens long ago…and offers to us part of our own heritage. By exploring and applying time-tested garden designs and plants modern Southern gardeners can profit from successes of their ancestors while creating beautiful and practical landscapes.

“We think of these plants as heirlooms, or living antiques because they are tangible symbols of success for generations of Southern gardeners. Many have been lovingly handed down among the families that contribute cultural diversity and richness to our gardens The fact that these plants have been time-tested in our Southern climate and soils over a long period makes their use in today’s gardens a compelling choice. As we become more and more a nation of gardeners, the successful traditions and plants of our ancestors offer a unique opportunity from which to reflect and build our future.

“Also of great interest and significance to Southern gardeners is information on the impact of many different cultures – Native American, English, French, Spanish, German and African-American – on the South. It is as important to know where we came from, and how, as it is to plan for future change. Regional diversity and ethnic influences survive to this day, chronicled through plants such as poet’s laurel, sweet myrtle, pomegranate, banana shrub, cape jasmine, jujube, camellia, chinaberry or the magnolia fig. Swept yards, parterres of boxwood hedges, knot gardens, hen yards dotted with umbrella chinaberry trees or small plumtrees, planters created from whitewashed tires, or even bottle trees and bottle edgings created from castoffs – all have different stories to tell.”

I grow antique roses. I love them for several reasons, but I must admit that one of my main reasons for loving them is that they are a link to an earlier time in history.